Alarms with operator response can serve as an Independent Protection Layer (IPL) with a Probability of Failure on Demand (PFD) of 0.1, provided that independence requirements are met. However, if the initiating cause originates from the Basic Process Control System (BPCS), careful assessment of independence is required, especially when alarms are also managed by the BPCS.

Ensuring Independence of Alarm

For an alarm to be considered sufficiently independent, the following conditions must be met:

- The hardware components linked to the initiating cause—such as transmitters, final elements, communication networks, and I/O cards—must not be associated with the alarm system.

- The initiating cause must not involve operator error, as the same operator is expected to respond to the alarm.

The reasoning behind this is that the BPCS itself, the only shared component between the cause and the alarm, has a lower probability of experiencing an undetected failure compared to other potential failure causes. Furthermore, a failure in the BPCS would likely trigger multiple disturbances that the operator would recognize.

Key Considerations for Operator Response

For an alarm to be an effective IPL, the operator’s response must be both feasible and independent. The following factors should be taken into account:

1. Operator Safety

The operator must not be exposed to hazardous conditions while responding to the alarm. For example:

- If an overpressured vessel or overspeeding compressor poses a risk, the operator should not be required to approach it directly.

- Simple engineering solutions, such as fitting a valve handle with an extended shaft, can allow remote operation from a safe distance.

2. Independence from Safety Instrumented Functions (SIF)

Shutting down electrical equipment must use a method that is independent from any SIF that also shuts down the equipment. Actions taken by the operator should be independent of any SIF controlling the same equipment. For instance:

- If an operator needs to shut down electrical equipment, they should have direct access to the circuit breaker rather than relying on an interlocked system.

- Motor Control Centers (MCCs) often have two independent trip inputs, one linked to the Safety Instrumented System (SIS) and the other to the BPCS. These are generally considered sufficiently independent since they act through few common components inside the MCC.

3. Operator Availability

The operator must be present whenever the initiating event may occur. This requirement may not be met if:

- if the site is not continuously manned

- The operator is engaged in other critical activities, such as warehouse management or tanker offloading.

4. Adequate Response Time

The operator must have enough time to react between alarm activation and the point of no return. The concept of process safety time determines this margin.

If the operator can respond from the control room by taking an action in the BPCS (e.g. adjusting a control loop or operating a remote-operated valve), then the response time required can be relatively short: typically, a minimum response time requirement of 10~15 mintues is defined in the SIL assessment procedure or alarm philosophy document.

However, if action is required by a field operator, the response time requirement could be considerably longer. To demonstrate that an alarm is a valid IPL, the SIL assessment team must consider the response time available and the response time required on a case-by-case basis.

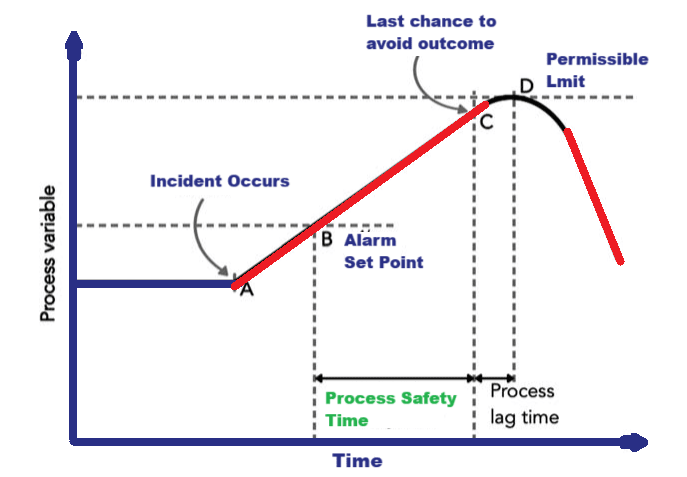

Alarm Response Time and Process Safety Time

An alarm can be considered a valid IPL only if the response time is within the available process safety time. The Process Safety time is the time between the alarm triggering and when corrective action must be completed to prevent an undesired event.

Illustration of Process Safety Time

- Point A: An Incident occurs, causing a process variable (e.g., temperature, pressure, or level) to move toward its permissible limit.

- Point B: Alarm activates, signaling the operator to take corrective action.

- Point C: is the latest possible time to complete the operator’s action if the process variable is to avoid over-shooting the permissible limit at point D.

- Point D: It is the permissible limit, where if the process variable exceeds this permissible threshold, it leads to potential failure or hazardous consequences.

- The time between points C and D is the process lag time, i.e. the time for the process to respond to the operator’s action. The curve shows the ‘worst case’ scenario in which the alarm response time is equal to the process safety time.

Credit for Alarms as an IPL

In most scenarios, credit should only be assigned to one alarm per event since a single operator and human-machine interface (HMI) are involved. However, exceptions exist. A local field alarm with a fully independent operator can be considered for additional credit.

For example, during a truck-to-tank transfer, if overfilling occurs:

- A local high-level alarm from a separate sensor can alert a field operator or truck driver.

- The independent operator can take direct action, such as closing the truck’s outlet valve.

- This prevents hazardous consequences, such as a fire due to an overfilled storage tank.

By ensuring proper independence, availability, and response feasibility, alarms with operator response can serve as an effective and reliable Independent Protection Layer in process safety management.

References:

Functional Safety from Scratch by Peter Clarke